I've been practicing test driven development for a number of years now but the approach I take has changed dramatically over time. One particular type of test that I became fond of as I started writing single page apps with emberJS was the acceptance test. Without this higher level of testing I never felt confident that my JavaScript application would actually boot up, route as expected, make fetch requests to hydrate my components, etc.

And for 3 years or more I test drove nearly 100% of the functional requirements using this type of test exclusively. I found this technique provided me with the freedom to refactor almost anything without fear of breaking a test. This attribute was especially important to me at the time because of a painful experience I had maintaining a test suite chock-full of mock objects in a past life.

And while this approach felt like a silver bullet at first, I started to identify some downsides as teams and test suites grew over time.

Failure locale

When a test would fail you suddenly had a large surface area to look for root cause. Was this something in the route? Or maybe the component(s)? Is this related to some async behavior? Did we pull in a patch of some 3rd party library that isn't playing nice?

The challenge here is that less experienced developers, or even someone new to the team, will often find solving a test failure less intuitive. And this firmly contradicts my belief that tests should provide support for new team members. Instead, because of all the moving parts involved, this team member now has an opportunity to get lost in the detailed inner workings of your application architecture.

Feedback loop

The selling point of acceptance testing is that you know how a given feature of the software works end to end. But as a developer my day is full of many micro decisions that benefit from a small and focused feedback loop optimized for experimentation and learning.

Say I decide to write a data driven html component that only shows a set of configured columns. I've determined that I need to write a computed property that can derive this new state. Acceptance testing alone encourages me to take many (more) steps before I get any feedback about my progress. If instead I write an integration or unit test I can get rapid feedback increasing my ability to try things and fail fast.

Grep-ability

Say you need to alter the behavior of an existing web component. How easy is it to find the tests that exercise it? The best teams I've been a part of generally organized the acceptance tests in one of two ways.

By Url As your application grows you often find that the tiny single page app you started with is more like 10+ apps all driven from a different url. One upside of organizing the acceptance tests by url is that if you decide to extract the production code, you've almost certainly got a test folder you can move with it to confirm all the functionality.

By Feature If you have a specific workflow for example you might categorize and group the test code associated with it. In this way you create pockets of knowledge that act as living documentation.

With either approach it can be difficult to quickly and easily identify what acceptance tests are helpful as you begin to refactor one specific component for example. Because acceptance tests are driving pages they almost certainly involve a dozen components or more in a variety of configurations.

If you have the opportunity to co-locate components with their tests it will greatly reduce the friction you would feel otherwise.

Async hell

Because acceptance tests exercise all parts of the running application you will almost certainly bump into a setTimeout or animation that can make the test suite unpredictable. This situation is often made worse when you try to retrofit a test suite for a legacy web application because of all the moving parts involved and the lack of foresight with respect to testability.

The struggle here is that if your test suite is not reliable it will slowly erode developer confidence in testing altogether. And rightfully so as tests should speed up velocity not grind teams to a halt. The moment someone on your team says "oh just trigger another build -that might work" you've started to chip away at the developer confidence corner stone. If you find yourself in this situation, do your best to course correct quickly before developers associate testing with inconsistency.

The human tax

Any software product team with > 1000 tests will find out sooner or later that maintaining a test suite like this can easily soak up 1 person part time (or even full time depending on the number of teams/ number of tests/ complexity of the UI/ quality of test cases/ etc). Worse yet, the person who can play this role effectively is often one of the most experienced UI engineers on staff ...meaning they are no longer building features for the product.

I know this role all to well because I played it myself not all that long ago. Often the process is slow going but a year or so in and you've built your own prison. If this role is a must be sure to rotate it often and find some way to leverage it as a mentoring opportunity intended to grow less experienced engineers.

What /should/ we do instead?

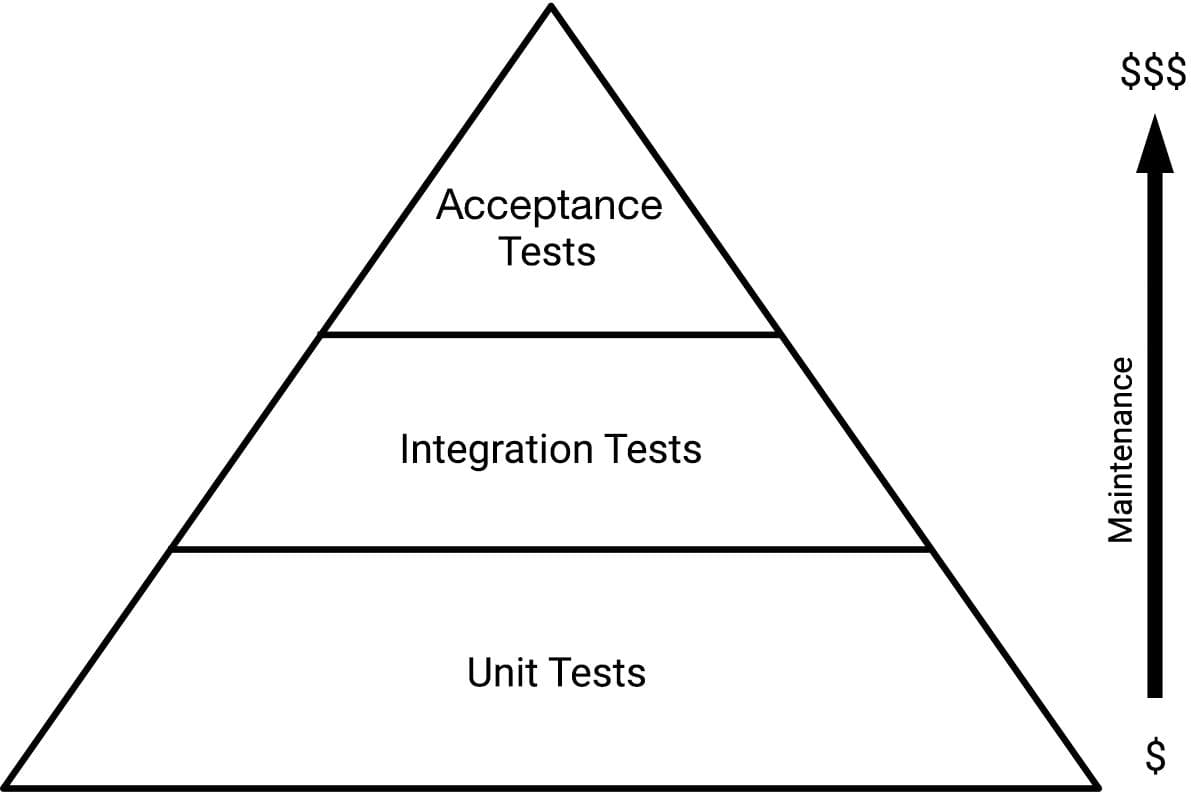

I'm not advocating we completely throw out acceptance testing. Instead I'm asking that we become educated about the cost of these tests and find alternatives that provide greater return on investment.

The past few months I've started test driving my features with (component) integration tests instead. The positive experience I've had with this approach has everything to do with the test focus shifting from pages (of components) to a single component.

I still work outside in with the emphases on fast feedback. I even write the occasional acceptance test but these days I don't start with the assumption that everything /must/ be driven from the top down with acceptance testing. And if I do decide to write an acceptance test I better understand the burden I will be placing on the team.